Short and squatty with a handle that pulled out to open the door, Grandmother’s Frigidaire is home to an important piece of my family history, a story of a first and a last . . .

The first and only time Grandmother Hewell told me “No” was the day I – the apple orchard of her eye – reached to the back of the squatty, boxy, white-on-the-outside-turquoise-on-the-inside refrigerator intending to help myself to the Zero candy bar in the back left corner of the second shelf. Her loud, abrupt “NO” startled me. She offered no explanation, just “You leave that alone,” as she pushed me to the side and closed the refrigerator door.

I was stunned. Grandmother had never denied me anything – not a single thing. My wish was her command, and I didn’t have to clean some funny-shaped lantern to get her attention. But that fateful day, all I got was a resolute, unwavering NO.

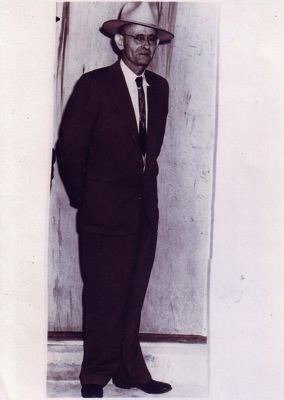

Crawford Jr. plays with 6 month old Baby Gene

William Eugene Hewell – was he my uncle or is he my uncle? I never know whether to use past or present tense when talking about people who are so alive inside me but aren’t readily available to hug or sit beside or laugh with.

Laugh with.

Everybody I ask to tell me about my Uncle Gene says the same three things:

~ I can’t think of him without seeing him sitting up on that tractor seat.

~ I remember him popping wheelies in the front of the school before the bell rang.

~ He was funny. Lord a-mercy how that man did make us laugh. I never knew anybody as funny as your Uncle Gene.

William Eugene Hewell was born on March 31, 1933, a mere five weeks before five armed bandits held the family hostage while waiting on the bank’s vault to open so they could relieve it of its money bags. Uncle Gene was the last of five children born to Grandmother and Granddaddy. Before him, there was Juanita who lived 4 days. Edgar and Earl were twins, one living for an hour, the other stillborn. Then there was Crawford Junior, my daddy. He was five when Uncle Gene was born.

12 year old uncle Gene behind the wheel of the tractor

Zero candy bars were Uncle Gene’s favorite. The morning of December 19, 1951, he pulled the handle to open the refrigerator door, placing his beloved Zero candy bar in the back left corner so it would be nice and cold when he came in later that afternoon. He kissed his mother on the cheek, said something to make her laugh and shake her head, then went out the back door. He hopped up on the tractor and headed off to spend the day pulling stumps up on the property. Though I can’t imagine how he reached the pedals, family lore – those sacred stories that remain forever impervious to logic – holds that Uncle Gene learned to drive a tractor when he was 8 years old. Two years later, Granddaddy began renting out the tractor, sending Uncle Gene along to operate it. Details aside, it stands true that Uncle Gene knew his way around tractors.

But this day, something went terribly, horribly, unspeakably wrong.

He put the chain too high up on the stump, some tell me. Others say he put the chain too low. Either way, the result remains the same. As Uncle Gene began to move the tractor forward, it reared up and flipped over on him, crushing him instantly. I am told that my wiry, small-framed granddaddy found my rotund uncle, lifted the tractor off him, and carried Uncle Gene back to the house where he laid him on the bed he shared with my grandmother.

Granddaddy Hewell drove a silver stake in the ground to mark the spot. Grandmother kept that Zero candy bar as her private refrigerator memorial to the son she loved to immensely. Years later, Crawford created his memorial to his brother Gene by naming his firstborn child after him. He spelled her name Jeanne.

P.S. Uncle Gene died on December 19, 1951. Twelve years later to the day, Granddaddy Hewell died. He died in his sleep, and because the attending doctor couldn’t be sure whether he died before or after midnight, he chose to let Granddaddy’s death stand forever as the same day his younger son was killed.

P.S. 2 I am currently writing a book about what happened to my family on May 5-6, 1933 and having a big time as my daddy would say, learning more about myself as I look back at those who preceded me.

Other Places to Find Us